History of the Association

Brief introduction to the foundation of the AIDLR

1. Its founder

Jean Nussbaum, a French physician of Swiss origin, founded the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty, abbreviated as A.I.D.L.R., in Paris, in 1946. His wish was to give a legal basis to the actions he had been taking on behalf of religious liberty, since the end of World War I.

Jean Nussbaum, the founder.

Jean Nussbaum was born in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, on November 24, 1888. He had a medical practice in Chamonix, France, when World War I broke out. Serbia, plagued by a strong outbreak of typhus from the very beginning of hostilities, made a desperate appeal to foreign countries to secure the help of physicians. Jean Nussbaum volunteered and was appointed to the hospital of Nis, Serbia, near the end of 1914. The management of the hospital gave him a young Serbian nurse, Milanka Zaritch, as an assistant and interpreter. Soon after their first meeting, she became the superintendent of the hospital.

They married in the fall of 1915. Milanka Zaritch was the niece of Voyislav Marinkovic, who later became the prime minister of the Serbian government. This family link soon introduced Dr Jean Nussbaum into the diplomatic and international circles.

While he was in Serbia, circumstances led Jean Nussbaum to an intervention with an officer of the Serbian army, to allow an Austrian prisoner of war, appointed to serve in the Nis hospital, to practice the principles of his faith. Out of lack of tact and narrow-mindedness, this prisoner had placed himself in a situation which might have cost him his life by refusing, as an enemy prisoner and in time of war, to obey orders. This event may have been instrumental in the awakening of the interest Jean Nussbaum was taking in the promotion and defense of liberty of conscience and religion for the rest of his life.

Back to Switzerland, then to France, Jean Nussbaum opened a medical practice in Le Havre, France. Fifteen years later, in 1931, he and his wife settled in Paris, where he remained till his death in 1967. There he opened, in 1946, the first headquarters of the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty.

The couple had been living in Paris only for a few months when Dr Jean Nussbaum was invited by the religious circles to take part in a debate about a project to reform the world calendar. This project was to be presented in October, 1931, during the plenary session of the fourth International Convention of Transport and Communications held in Geneva by the League of Nations. The Preparatory Commission of this Convention had stated, in its preliminary report, that the delegates meeting in this session had presented no argument maintaining that the proposed reform was incompatible with religious practices. The representatives from religious circles had therefore been invited to present their points of view. While the representatives of the nations considered this issue from an economical and social point of view, most religious observers had understood, however, that it concerned millions of believers in the world, particularly Christians, Jews and Moslems.

In a report on this Convention, dated October 14, 1931, Joseph Herman Hertz, Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community in the British Empire, narrated Dr Jean Nussbaum’s intervention:

“He [the physician] earnestly requested the representatives to remember that it was an important issue of conscience, and that any interference with human conscience was incompatible with the ideals of the League of Nations. All previous interventions of the observers had been made in English, and several delegates had only been able to follow them through a translation. This masterly intervention in French, however, went to their hearts.”

Two years later, Dr Jean Nussbaum was elected by the plenary session of the delegates of the Southern European Division of the Seventh-day Adventist Church to be the director of its Department of Religious Liberty. While pursuing his medical practice, he began working on behalf of religious liberty. He was supported by several international personalities. The most significant of them was undoubtedly Pope Pius XII, with whom he had been maintaining a friendly relationship while he was still Cardinal Pacelli. Dr Nussbaum dedicated also part of his time to the International Religious Liberty Association, with headquarters in Washington.

After World War I, the political restructuring of Central Europe, from the Danube to the Balkans, with its economical, social and religious implications, produced many hardships for the Christians of several nations of this part of the world.

In his personal notes on his activities, Jean Nussbaum gave an account on the visits which he had paid to political and religious personalities in Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Yugoslavia. But he also travelled widely in Spain, Ethiopia, France, Great Britain, Greece, and Italy. His attention was even drawn to the situation in Japan. His interventions were on behalf of Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox Christians facing difficulties.

In Oxford, in July, 1937, Nussbaum met, for the first time, Marc Boegner, a Protestant theologian and member of the Académie française, who was then the president of the French Protestant Federation. They remained friends till Dr Nussbaum’s death. These two men shared deep appreciation for each other, although their opinions on how to protect religious liberty were different.

2. The Foundation of the Association

On April 25, 1945, Jean Nussbaum attended the United Nations Convention in San Francisco. Its goal was to found an international organization to succeed the League of Nations. The Economical and Social Council was appointed to deal with the topics concerning the human rights. There he met Mrs Eleanor Roosevelt, the widow of the former president of the United States. These two persons quickly agreed on the issues of human rights. It brought them closer to each other in the battle they were both fighting and fostered their cooperation in the years that followed:

“[…] every time he went to the USA, namely once a year at least, Dr Nussbaum was hosted by Mrs Roosevelt and her sons, in their estate. When she came to Paris, she used to lodge at Hotel Crillon and had several meetings with the physician, who organized suppers at his home, Avenue de la Grande Armée, or in the city.”

Jean Nussbaum mentioned his project to found the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty in Paris. He expressed the wish that she should be its first president. The American authorities agreed.

In 1948, Jean Nussbaum founded the Conscience et liberté [Conscience and Liberty] magazine and published the first three issues himself. A tireless worker, he gave numerous lectures on the issue of religious liberty. He recorded radio broadcasts on this issue. André Dufau, his main assistant in the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty from 1950 through 1966, wrote in 1988:

“After World War II, as soon as 1946, he made use of the radio to disseminate the ideas of religious liberty which the world needed so badly. For almost one decade, Radio Monte Carlo broadcast a weekly program named “Conscience and Liberty”. Statesmen and diplomats spoke in these programs, and also specialists like Mr Emile Léonard, a teacher at the Sorbonne University, Miss Michèle-Marie Morey and Mr Raoul Stéphan, both professors “agrégés” at the French University. He also expressed his hope, over the radio, for a more tolerating and brotherly society, and gave a report of the results of his efforts and travels.”

Jean Nussbaum finished his activities only a few months before his death. On October 29, 1967, he died of a heart attack, aged 79.

When, in 1945, during a stay in San Francisco, Dr Nussbaum was asked by the French minister, Jean-Paul Boncour: “What interests do you defend?” he answered: “I do not defend any interests, but a principle: the principle of religious liberty.”

3. The Philosophy of the Association

In 1948, two years after the foundation of the Association, Jean Nussbaum wrote:

“The goal of the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty is to disseminate, all over the world, the principles of this fundamental liberty and to protect, in all legitimate ways, the right of every man to worship as he chooses or to practice no religion at all. Our Association doesn’t represent any particular church or political party. It has assumed the task of gathering all spiritual forces to fight intolerance and fanaticism in all their forms. All men, whatever their origin, color of skin, nationality or religion, are invited to join this crusade against sectarianism if they have a love for liberty. The work lying ahead is immense, but will certainly not go beyond our strength and means if everybody gets down to work, with courage.

“We are thus implementing ecumenism, on a special level, and in a very comprehensive way; for we are not only appealing to the Christians in the whole world, but also to the believers of all religions. We even hope that our appeal will also be heard by those who have no religion. Why shouldn’t they join us?”

4. The Honorary Committee

It has already been mentioned that the first president of this Association was Mrs Eleanor Roosevelt. André Dufau wrote about her: “She accepted to be the president of the Honorary Committee of the new Association, [...] which included distinguished personalities, as, for instance, Edouard Herriot, the president of the French National Assembly, and members of the French Academy, such as Paul Claudel, Georges Duhamel, André Siegfried, and Duke Louis de Broglie.”

As soon as it was founded, the Association was supported by illustrious individuals from the university, religious and political circles. Several of them were its presidents. Following Mrs Eleanor Roosevelt, the next president was Dr Albert Schweitzer, a French physician, a member of the French Academy, and Nobel Peace Prize holder; then, in 1966, Paul-Henri Spaak, a Belgian politician and former minister at the Foreign Office, who had played an important part in restructuring post-war Europe. From 1974 through 1976, it was René Cassin, a lawyer and member of the French Institute, who was also awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1968. Besides, René Cassin was one of the initiators of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, of 1948. In 1977, the Association was presided by Edgar Faure, a French lawyer and former president of the Council of State as well as Education Minister till his death in March 1988. Léopold Sédar Senghor, former president of the Republic of Senegal and member of the French Academy, presided the Association from 1989 through 2001. The current president is Mrs Mary Robinson, former High Commissioner for Human Rights and former president of the Republic of Ireland.

5. Geographical Scope

In 1966, the international headquarters of this Association were transferred from Paris to Berne, Switzerland. This move was necessary to meet the needs of a closer proximity to the meeting places of the UN Commission on Human Rights and its Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, with headquarters in Geneva, in the Palace of the United Nations.

From 1973 on, new national sections were founded in several European and African countries, and, from 1990 through 1995, in the countries of Eastern Europe, such as Romania, Bulgaria and the Czech Republic. A new national section is in the process of being founded in Cameroon.

6. Official Recognition

In 1978, the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty was given the statute of a non-government organization (NGO) by the United Nations. It obtained a participative statute from the European Council, in 1985.

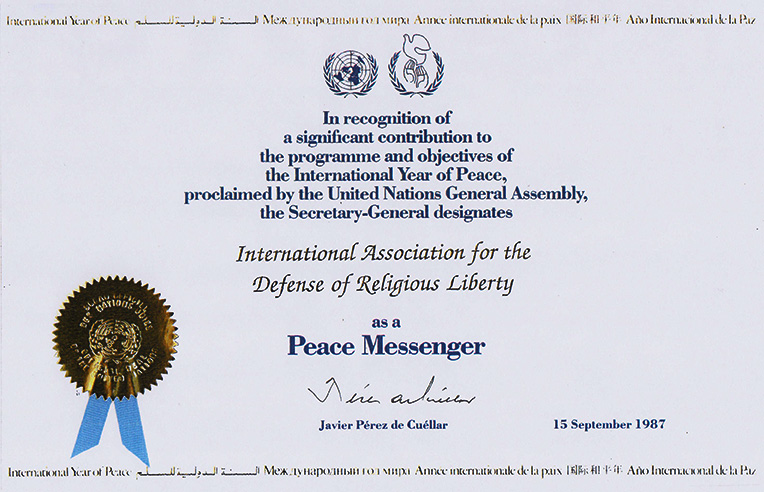

On September 15, 1987, within the framework of the International Year of Peace, Mr Pérez de Cuéllar, the then Secretary General of the United Nations, conferred on the Association the title of “Messenger of Peace”.

On April 27, 1998, its general secretary, Maurice Verfaillie, was awarded the Cross of Commander of the Order of National Merit, conferred by the King of Spain, Juan Carlos.

7. Activities

Since its foundation, this Association has been active in four realms: maintaining relations with political, civil, religious and academic personalities; keeping contacts with the international organizations; organizing or attending national and international seminaries, conventions, symposiums on issues of liberty of conscience, religion or conviction; publishing the Conscience et liberté [Conscience and Liberty] magazine.

The Association has contributed actively in preparing the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief, adopted by the United Nations in 1981. It has also cooperated with the Commission on Human Rights which, in its General Comments on Article 18 of the International Agreement on Civil and Political Rights, specified that the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion “includes the freedom to have or adopt a religion or belief of one’s own choice, and the freedom to manifest one’s religion or belief, individually or in community with others, and in public or private”.

8. Conscience et liberté [Conscience and Liberty] magazine

The best-known contribution to the reflection and promotion of the fundamental right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion of the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty is the publication of its official organ, the Conscience et liberté [Conscience and Liberty] magazine. This magazine is indexed in the libraries of many universities, international or religious organizations, throughout the world.

From its very beginning, the editors’ policy has been to promote a magazine with an academic, non-denominational and pluralistic character.

This magazine is published in French, German, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, and Romanian. The first issue in Bulgarian went off the press in December, 1998, and in Czech in 2005.

From 1949 through 2006, Conscience et liberté [Conscience and Liberty], in its French edition, has published 984 articles and studies on the foundations, history and implications of religious liberty, 237 documents and 504 news items. By the end of 2006, a total of 536 authors of 70 different nationalities and coming from a wide academic, political or religious spectrum, had written articles and studies for the magazine.

9. Financial resources

The budget of the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty, in Berne, is supplied by the contributions of the national chapters and the subscriptions to the Conscience et liberté [Conscience and Liberty] magazine. The donations and contributions help to cover the operating costs and the publication of the magazine.